STUXnet – Just a virus?

STUXnet – Just a virus?⌗

Well, let us investigate the past geopolitical scenarios first before diving into the topic. Early 1950s. Iran’s nuclear program beg an but in a slow state. The US supplied the Tehran Nuclear Research Centre (TNRC) with a small 5MWt research reactor fuelled by Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) in 1967. In ‘73, the Shah unveiled ambitious plans to install 23,000Mwe of nuclear power in Iran by the end of the century, charging the newly founded Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) with oversight of this task. In the following years, Iran concluded several technology related contacts with foreign suppliers and invested in education and training for the same. By the 1979 revolution, Iran had developed good baseline capability in nuclear technologies.

Fast forward to 1980s. Iran signed long-term nuclear cooperation agreements with Pakistan and China in 1987 and 1990 respectively. From multiple countries Iran received nuclear research supplies and equipment.

U.S. Intelligence have long suspected Iran of using its civilian nuclear program as a cover for clandestine weapons development. U.S. government has actively pressured potential suppliers to limit nuclear cooperation with Iran. China did not ultimately supply Iran with the reactor (which would have been ideal for plutonium production). Iran’s agreement with Argentina for uranium enrichment and heavy water production facilities was blocked.

In early November 2004, the CIA received thousands of pages of information from a “walk-in” source indicating that Iran was modifying the nose cone of its Shahab-3 missile to carry a nuclear warhead. Furthermore, in early 2004, the IAEA discovered that Iran had hidden blueprints for a more advanced P-2 centrifuge and a document detailing uranium hemisphere casting from its inspectors.

There was enough reason for the other countries not to trust Iran with the nuclear plans. Wait, you expected a technical blog, but you are tired of reading history? Well, yeah, this part was necessary.

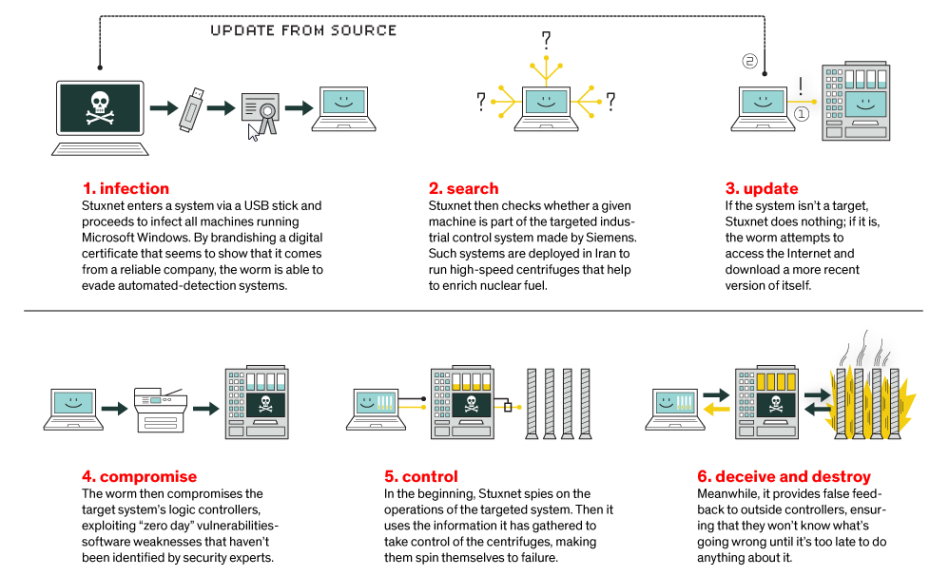

In June 2010, the STUXnet worm was jointly engineered by the United States and Israel to cripple Iran’s nuclear efforts. It was proposed in 2006 under the code name of “Olympic Games”. A virtual replica of Iran’s Natanz Nuclear Plant was built at American National Laboratories. It has been the most complicated computer worm the world has seen till date. Generally, computer viruses have a gibberish of code to hide misguide the security researchers. However, STUXnet was different. Every command had something particular to do.

When it particularly became available to security researchers, it took many days for them to even understand the tip of the iceberg. Gradually, the researchers at mainly Symantec Laboratories and Kaspersky Laboratories worked for hours to days to go through it. Analysing keyword, some prominent words came up, like .STUB and one of the rootkits used like mrxnet.sys, giving rise to the word STUXnet.

As the name suggests, .sys file. This file usually resides in

%SYSTEMROOT%/Windows/System32/Drivers/mrxnet.sys

easily proving that this malware targets Windows based computers only.

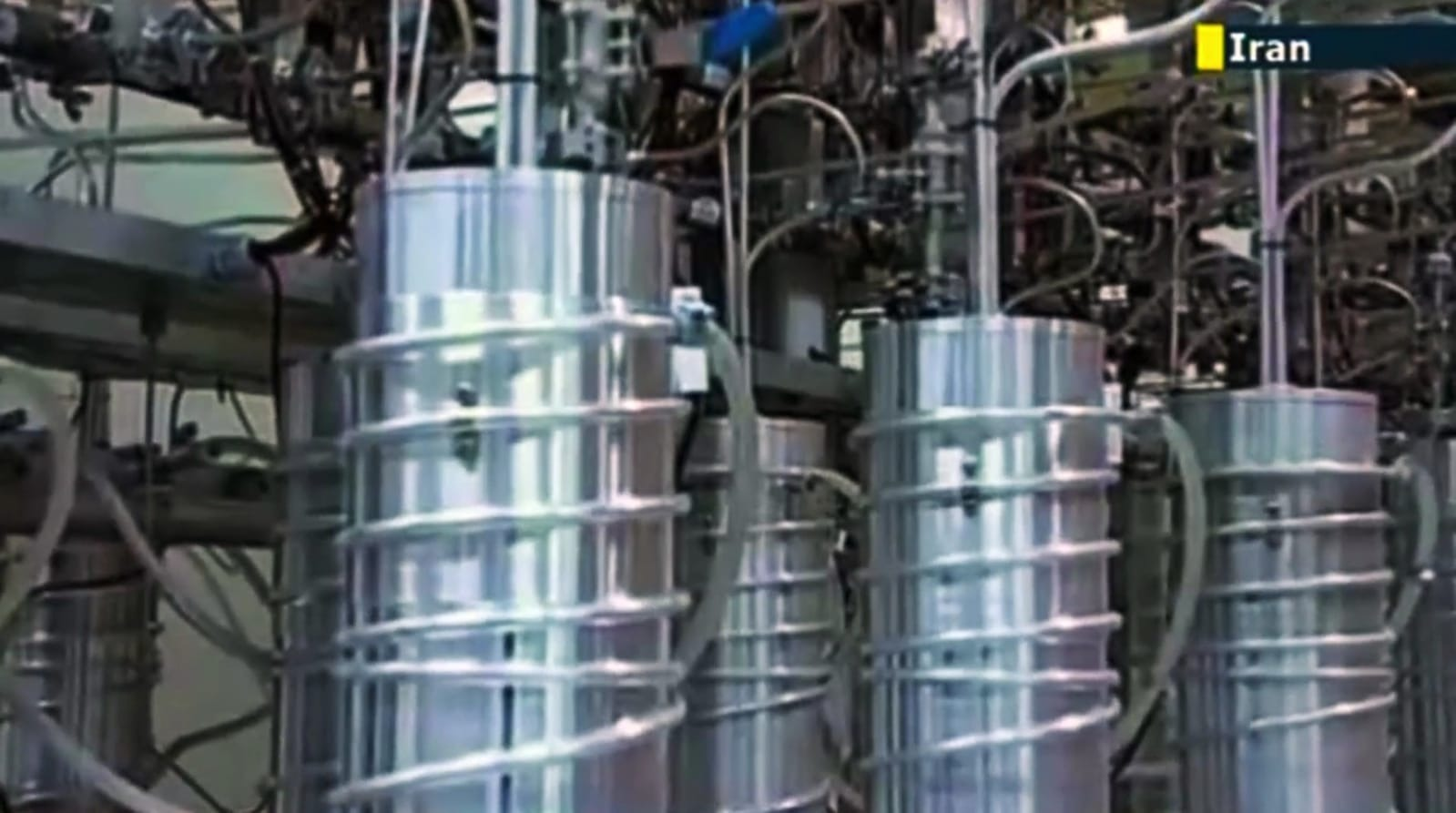

Back to Iran, the nuclear plant had 6 groups of centrifuges, each having 164 centrifuges. On the other hand, it was clearly visible that the STUXnet program was using an Array of size 6 objects and each of those objects had 164 elements.

On further research, it was seen that STUXnet mainly targeted some Siemens PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) connected to the computers. To be more specific, the Siemens S7-3000 system and its associated modules. It was the same device that was used in centrifuges in the Iran nuclear plant.

STUXnet is essentially a zero-day malware, meaning it would spread and infect automatically without the use of users having to take some action like download a file or open a link. It used to spread through infectious viruses.

Now, the question comes, how did it reach the Iran nuclear plant? Well, it was under study of the U.S Intelligence that which company assisted the nuclear plant with IT and technical support. The machines of that company were first infected and then it started spreading though infected flash drives, thus reaching the nuclear plant.

The plan of the nuclear plant was simple. There was a hall that contained the centrifuges and near to it, there was the controller’s room from where they were controlled. The centrifuges essentially controlled the electric motors which were controlled by the PLCs.

After infecting the target computer, STUXnet remained dormant for thirteen days. In these days, it simply recorded the normal activities. Also, it was the time for the enrichment process, that is the time taken to fill the centrifuges with uranium. Generally, the safe speed for the motors was 63000 RPM, which is about a 1000Hz. STUXnet caused them to speed up to 14000Hz, which matched with the resonance frequency of the centrifuge. Then suddenly it was slowed down to 2Hz, which is basically close to a standstill. As the result, these centrifuges started to wobble and ultimately collapse. Moreover, STUXnet had also jammed the feedback mechanisms. The feedback mechanisms of the PLCs would try to send the real state of the centrifuges to the controller’s computer. However, what STUXnet did was send back the data that was recorded in the 13 days of dormancy.

After some time, obviously the computer would show everything to be fine, but the operators could hear the noise made by the centrifuges. They would try to stop it but STUXnet had eventually overridden that as well.

STUXnet had taken 984 centrifuges out of service and essentially causing a huge setback to Iran’s nuclear program.

How Stuxnet works

Stuxnet is a threat that was primarily written to target an industrial control system or set of similar systems. Industrial control systems are used in gas pipelines and power plants. Its final goal is to reprogram industrial control systems (ICS) by modifying code on programmable logic controllers (PLCs) to make them work in a manner the attacker intended and to hide those changes from the operator of the equipment. In order to achieve this goal, the creators amassed a vast array of components to increase their chances of success. This includes zero-day exploits, a Windows rootkit, the first ever PLC rootkit, antivirus evasion techniques, complex process injection and hooking code, network infection routines, peer-to-peer updates, and a command-and-control interface. We take a look at each of the different components of Stuxnet to understand how the threat works in detail while keeping in mind that the ultimate goal of the threat is the most interesting and relevant part of the threat.

Stuxnet analysis is rapidly concentrated on the level of the worm sophistication that goes to exploit several unknown vulnerabilities of windows servers (called “0-day”).

The infection spread through an infected device (USB pen-drive) inserted in a normal personal computer. Simply opening the window of “windows file explorer” the worm could spread in the operating system and next replicate itself through the network.

The worm is designed to spread through the network and attacks all vulnerable Microsoft windows systems (from NT4 to 7 version) whether the Microsoft security patch MS10-46 (available since 2 august 2010) was not applied in the operating system.

Once executed, Stuxnet hides his infected files into the USB stick using the “userland” rootkit that allow to hide in the filesystem all the file with “.lnk” extension and the file that starts with “~ WTR” and ends with “.tmp”.

But, as specified from Symantec analysis, the worm use both network sharing, and MS08-067 vulnerability to spread itself.

Features

-

Self-replicates through removable drives exploiting a vulnerability allowing auto-execution. (Microsoft Windows Shortcut ‘LNK/PIF’ Files Automatic File Execution Vulnerability (BID 41732))

-

Spreads in a LAN through a vulnerability in the Windows Print Spooler.

(Microsoft Windows Print Spooler Service Remote Code Execution Vulnerability (BID 43073)) -

Spreads through SMB by exploiting the Microsoft Windows Server Service RPC Handling Remote Code Execution Vulnerability (BID 31874).

-

Copies and executes itself on remote computers through network shares.

-

Copies and executes itself on remote computers running a WinCC database server.

-

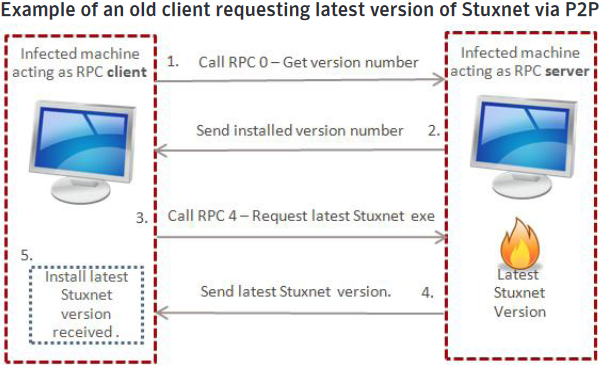

Updates itself through a peer-to-peer mechanism within a LAN.

-

Exploits a total of four unpatched Microsoft vulnerabilities, two of which are previously mentioned vulnerabilities for self-replication and the other two are escalation of privilege vulnerabilities that have yet to be disclosed.

-

Contacts a command-and-control server that allows the hacker to download and execute code, including updated versions.

-

Contains a Windows rootkit that hide its binaries.

-

Attempts to bypass security products.

-

Fingerprints a specific industrial control system and modifies code on the Siemens PLCs to potentially sabotage the system.

-

Hides modified code on PLCs, essentially a rootkit for PLCs.

Reconnaissance

First, the attackers needed to conduct reconnaissance. As each PLC is configured in a unique manner, the attackers would first need the ICS’s schematics. These design documents may have been stolen by an insider or even retrieved by an early version of STUXnet or any other malicious binary. Once attackers had the design documents and potential knowledge of the computing environment in the facility, they would develop the latest version of STUXnet. Each feature of Stuxnet was implemented for a specific reason and for the final goal of potentially sabotaging the ICS.

In addition, their malicious binaries contained driver files that needed to be digitally signed to avoid suspicion. The attackers compromised two digital certificates to achieve this task. The attackers would have needed to obtain the digital certificates from someone who may have physically entered the premises of the two companies and stole them, as the two companies are in close physical proximity.

Architecture

The heart of Stuxnet consists of a large .dll file that contains many different exports and resources. In addition to the large .dll file, Stuxnet also contains two encrypted configuration blocks.

The dropper component of Stuxnet is a wrapper program that contains all of the above components stored inside itself in a section name “stub”. This stub section is integral to the working of Stuxnet. When the threat is executed, the wrapper extracts the .dll file from the stub section, maps it into memory as a module, and calls one of the exports.

A pointer to the original stub section is passed to this export as a parameter. This export in turn will extract the .dll file from the stub section, which was passed as a parameter, map it into memory and call another different export from inside the mapped .dll file. The pointer to the original stub section is again passed as a parameter. This occurs continuously throughout the execution of the threat, so the original stub section is continuously passed around between different processes and functions as a parameter to the main payload. In this way every layer of the threat always has access to the main .dll and the configuration blocks.

In addition to loading the .dll file into memory and calling an export directly, Stuxnet also uses another technique to call exports from the main .dll file. This technique is to read an executable template from its own resources, populate the template with appropriate data, such as which .dll file to load and which export to call, and then to inject this newly populated executable into another process and execute it. The newly populated executable template will load the original .dll file and call whatever export the template was populated with.

Although the threat uses these two different techniques to call exports in the main .dll file, it should be clear that all the functionality of the threat can be ascertained by analysing all of the exports from the main .dll file.

Bypassing Behaviour Blocking When Loading DLLs

Whenever Stuxnet needs to load a DLL, including itself, it uses a special method designed to bypass behaviour blocking and host intrusion protection-based technologies that monitor Load Library calls. Stuxnet calls Load Library with a specially crafted file name that does not exist on disk and normally causes Load Library to fail. However, W32.Stuxnet has hooked Ntdll.dll to monitor for requests to load specially crafted file names. These specially crafted filenames are mapped to another location instead—a location specified by W32.Stuxnet. That location is generally an area in memory where a .dll file has been decrypted and stored by the threat previously. The filenames used have the pattern of KERNEL32.DLL.ASLR.[HEXADECIMAL] or SHELL32.DLL.ASLR. [HEXA-DECIMAL], where the variable [HEXADECIMAL]is a hexadecimal value.

Injection Technique

Whenever an export is called, Stuxnet typically injects the entire DLL into another process and then just calls the particular export. Stuxnet can inject into an existing or newly created arbitrary process or a preselected trusted process. When injecting into a trusted process, Stuxnet may keep the injected code in the trusted process or instruct the trusted process to inject the code into another currently running process.

Rootkit installation

The worm continues his installation releasing different components on the infected computer, and in specific:

- A “Rootkit kernel” (implemented by the drivers mrxcis.sys and rxnet.sys) that hides the file used for the infection. This second rootkit, known as “TmpHider”, has the same effect caused by the first rootkit “userland”, the first executed by the worm, but it makes permanent modifications. Finally, another rootkit’s characteristic allows processes hiding.

- Two services (MRXCLS e MRXNET), which are not visible in the windows services list.

This part of Stuxnet installation works only if a user inserts an USB pen-drive in a computer using administrative privileges.

The rootkit, installed by Stuxnet, is partially furtive because it does not hide all file used. Indeed, with “Windows File Explorer” is possible find it searching the following files:

- %SystemRoot%system32driversmrxcls.sys

- %SystemRoot%system32driversmrxnet.sys

- %SystemRoot%infoem6c.pnf

- %SystemRoot%infoem7a.pnf

Important Exports

An export is called when the .dll file is loaded for the first time. It is responsible for checking that the threat is running on a compatible version of Windows, checking whether the computer is already infected or not, elevating the privilege of the current process to system, checking what antivirus products are installed, and what the best process to inject into is. It then injects the .dll file into the chosen process using a unique injection technique described in the Injection Technique section and calls the next export.

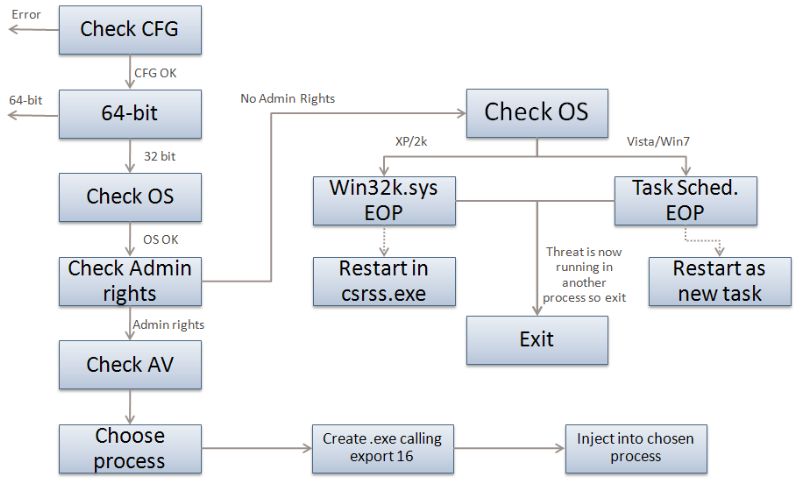

The first task in export is to check if the configuration data is up-to-date. The configuration data can be stored in two locations. Stuxnet checks which is most up-to-date and proceeds with that configuration data. Next, Stuxnet determines if it is running on a 64-bit machine or not; if the machine is 64-bit the threat exits. At this point it also checks to see what operating system it is running on.

Next, Stuxnet checks if it has Administrator rights on the computer. Stuxnet wants to run with the highest privilege possible so that it will have permission to take whatever actions it likes on the computer. If it does not have Administrator rights, it will execute one of the two zero-day escalation of privilege attacks mentioned.

If exploited, both of these vulnerabilities result in the main .dll file running as a new process, either within the csrss.exe process in the case of the win32k.sys vulnerability or as a new task with Administrator rights in the case of the Task Scheduler vulnerability.

The code to exploit the win32k.sys vulnerability is stored in resource 250.

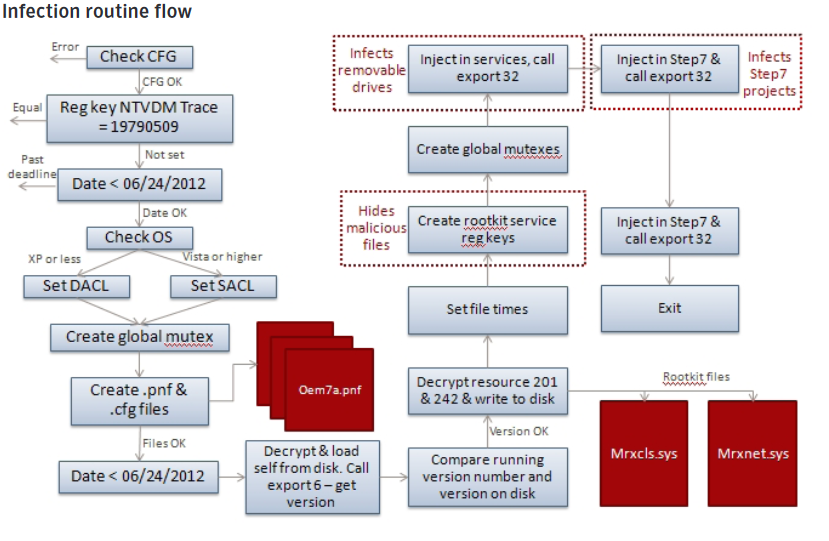

After the first export completes the required checks, The next export is called. It is the main installer for Stuxnet. It checks the date and the version number of the compromised computer; decrypts, creates and installs the rootkit files and registry keys; injects itself into the services.exe process to infect removable drives; injects itself into the process, sets up the global mutexes that are used to communicate between different components; and connects to the RPC server.

Network Propagation Routines

The Network Propagation export builds a “Network Action” class that contains 5 subclasses. Each subclass is responsible for a different method of infecting a remote host.

The functions of the 5 subclasses are:

1)Peer-to-peer communication and updates

2)Infecting WinCC machines via a hardcoded database server password

3)Propagating through network shares

4)Propagating through the MS10-061 Print Spooler Zero-Day Vulnerability

5)Propagating through the MS08-067 Windows Server Service Vulnerability

Network Communication

Once Stuxnet was installed, it attempts to communicate with the following two internet web sites using normal HTTP requests and TCP 80 default HTTP port:

Next then, it sends information about infected hosts (IP address, operating system, active services, etc.) to the previous two internet web sites. As response it can receive commands like:

- read, write, delete of infected host files

- Download and execution of a DLL from internet

- And so forth.

Evidently, when a SCADA system is infected, is unlikely that it is connected to internet. However, it is possible that one of the compromised servers has forbidden outgoing traffic towards public networks. This circumstance most likely would allow the dialogs between the infected machines and the internet servers.

Below is a graphical representation on the steps and spread of the worm:

Variants/Alias

Stuxnet has different variants and/or alias: roj/Stuxnet-A, W32/Stuxnet-B, W32. Temphid, WORM_STUXNET.A, Win32/Stuxnet.B, Trojan-Dropper:W32/Stuxnet, W32/Stuxnet.A, Rootkit.Win32.Stuxnet.b, Rootkit.Win32.Stuxnet.a.exet.

Countermeasures

Today, there are several countermeasures and tools to remove the malware and its variants.

- Symantec – W32.Stuxnet – Removal

- Hotforsecurity – Stuxnet Removal Tool

- BitDefender® – Stuxnet Removal Tool

- Microsoft Security Essentials

- Windows Defender

- Microsoft Windows Malicious Software Removal Tool

and the most effective techniques include:-

- Security Information and Event Management Systems (SIEM)

- Intrusion Monitoring Systems integrated with a SIEM system

- Implementation of a “Extrusion Detection” system

- Passive Vulnerability Scanner (PVS) into the network control system

Conclusion

Stuxnet represents the first of many milestones in malicious code history – it is the first to exploit four 0-day vulnerabilities, compromise two digital certificates, and inject code into industrial control systems and hide the code from the operator. Whether Stuxnet will usher in a new generation of malicious code attacks towards real world infrastructure overshadowing the vast majority of current attacks affecting more virtual or individual assets—or if it is a once-in-a-decade occurrence remains to be seen.

Stuxnet is of such great complexity—requiring significant resources to develop—that few attackers will be capable of producing a similar threat, to such an extent that we would not expect masses of threats of similar in sophistication to suddenly appear. However, Stuxnet has highlighted direct attack attempts on critical infrastructure are possible and not just theory or movie plotlines.

The real world implications of Stuxnet are beyond any threat we have seen in the past. Despite the exciting challenge in reverse engineering Stuxnet and understanding its purpose, Stuxnet is the type of threat we hope to never see again.